About Jodo Shinshu

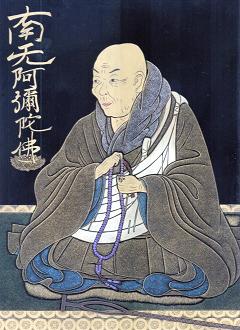

Jodo Shinshu is the teaching of Sakyamuni Buddha as it was handed down through the religious understanding of Shinran Shonin (1173-1262).

In Jodo Shinshu, the object of worship is Amida, the Buddha of Infinite Light and Life. The Primal Vow of Amida Buddha promises Universal Enlightenment for all beings. There is no other vow that has such sweeping power, promising hope and life’s fulfillment to all. Amida’s eternal activity of Wisdom and Compassion will never cease so long as beings are lost, suffering or wandering in a meaningless existence.

From the voluminous Buddhist Tripitaka, Shinran Shonin selected the following three sutras that bring us directly to the heart of Amida Buddha.

The Larger Sutra on the Eternal Life (Daimuryojukyo). In this sutra, Sakyamuni tells the Sangha about Amida Buddha.

The Meditation Sutra on the Eternal Buddha (Kammuryojukyo). This sutra shows the actual case of a woman who finds salvation through Amida Buddha.

The Smaller Sutra on Amida Buddha (Amidakyo). This sutra describes the beauty of the Pure Land.

The recitation of the Nembutsu – Namu Amida Butsu – the sacred Name of Amida Buddha is vitally important in Jodo Shinshu, for it is the core of Amida’s Vow. Amida Buddha communicates with us through his Name. Its form is twofold: it is Amida’s voice calling to us and at the same time is our vocal response to his call.

Jodo Shinshu regards Faith (Shinjin) as the only and sufficient cause for birth in the Pure Land and attainment of Nirvana. Shinran explained this Faith as the Faith of the Other Power, the Other Power being the Power of Amida’s Vow. From this, the Faith of the Other Power can be understood to mean the Faith bestowed by the Benevolence of Amida’s Vow. This interpretation of faith is the unique characteristic of Shinshu teaching.

Nembutsu, like Faith, is also bestowed by the Other Power or Amida’s Vow. Faith and Nembutsu given by the Other Power keep the followers from being attached to their own merits or power and help them enjoy the life of “Egolessness” and “Naturalness” which are fundamental ideas of Buddhism.

Shinran Shonin (1173–1263) was born at the close of the Heian period, when political power was passing from the imperial court into the hands of warrior clans. It was during this era when the old order was crumbling, however, that Japanese Buddhism, which had been declining into formalism for several centuries, underwent intense renewal, giving birth to new paths to enlightenment and spreading to every level of society.

Shinran was born into the aristocratic Hino family, a branch of the Fujiwara clan, and his father, Arinori, at one time served at court. At the age of nine, however, Shinran entered the Tendai temple on Mt. Hiei, where he spent twenty years in monastic life. From the familiarity with Buddhist writings apparent in his later works, it is clear that he exerted great effort in his studies during this period. He probably also performed such practices as continuous recitation of the nembutsu for prolonged periods.

Conversion

After twenty years, however, he despaired of ever attaining awakening through such discipline and study; he was also discouraged by the deep corruption that pervaded the mountain monastery. Years earlier, Honen Shonin (1133–1212) had descended Mt. Hiei and begun teaching a radically new understanding of religious practice, declaring that all self-generated efforts toward enlightenment were tainted by attachments and therefore meaningless. Instead of such practice, one should simply say the nembutsu, not as a contemplative exercise or means of gaining merit, but by way of wholly entrusting oneself to Amida’s Vow to bring all beings to enlightenment.

When he was twenty-nine, Shinran undertook a long retreat at Rokkakudo temple in Kyoto to determine his future course. At dawn on the ninety-fifth day, Prince Shotoku appeared to him in a dream. Shinran took this as a sign that he should seek out Honen, and went to hear his teaching daily for a hundred days. He then abandoned his former Tendai practices and joined Honen’s movement.

Exile

At this time, however, the established temples were growing jealous of Honen, and in 1207 they succeeded in gaining a government ban on his nembutsu teaching. Several followers were executed, and Honen and others, including Shinran, were banished from the capital.

Shinran was stripped of his priesthood, given a layman’s name, and exiled to Echigo (Niigata) on the Japan Sea coast. About this time, he married Eshinni and began raising a family. He declared himself “neither monk nor layman.” Though incapable of fulfilling monastic discipline or good works, precisely because of this, he was grasped by Amida’s compassionate activity. He therefore chose for himself the name Gutoku, “foolish/shaven,” indicating the futility of attachment to one’s own intellect and goodness.

He was pardoned after five years, but decided not to return to Kyoto. Instead, in 1214, at the age of forty-two, he made his way into the Kanto region, where he spread the nembutsu teaching for twenty years, building a large movement among the peasants and lower samurai.

Return to Kyoto

Then, in his sixties, Shinran began a new life, returning to Kyoto to devote his final three decades to writing. He did not give sermons or teach disciples, but lived with relatives, supported by gifts from his followers in the Kanto area. After his wife returned to Echigo to oversee property there, he was tended by his youngest daughter, Kakushinni.

It is from this period that most of his writings stem. He completed his major work, popularly known as Kyogyoshinsho, and composed hundreds of hymns in which he rendered the Chinese scriptures accessible to ordinary people. At this time, problems in understanding the teaching arose among his followers in the Kanto area, and he wrote numerous letters and commentaries seeking to resolve them.

There were people who asserted that one should strive to say the nembutsu as often as possible, and others who insisted that true entrusting was manifested in saying the nembutsu only once, leaving all else to Amida. Shinran rejected both sides as human contrivance based on attachment to the nembutsu as one’s own good act. Since genuine nembutsu arises from true entrusting that is Amida’s working in a person, the number of times it is said is irrelevant.

Further, there were some who claimed that since Amida’s Vow was intended to save people incapable of good, one should feel free to commit evil. For Shinran, however, emancipation meant freedom not to do whatever one wished, but freedom from bondage to the claims of egocentric desires and emotions. He therefore wrote that with deep trust in Amida’s Vow, one came to genuine awareness of one’s own evil.

Near the end of his life, Shinran was forced to disown his eldest son Zenran, who caused disruptions among the Kanto following by claiming to have received a secret teaching from Shinran. Nevertheless, his creative energy continued to his death at ninety, and his works manifest an increasingly rich, mature, and articulate vision of human existence that reveals him to be one of Japan’s most profound and original religious thinkers.

Copyright JODO SHINSHU HONGWANJI-HA 2002